TICAD is a Great Path to Sustainable Global Prosperity

For the seventh time in the last 25 years, African and Japanese leaders will meet again this month to chart the way forward for a future of shared prosperity for Africa, Japan and the world. Through Tokyo International Conference on African Development (TICAD), this August we will once again meet and root for multilateralism, underlining that in today’s interlinked world the destiny of the smallest nation on earth is intricately intertwined with that of the biggest nation on earth. By fostering African ownership of a development process backed by international partnerships, TICAD serves as one of the great examples of how to achieve Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

I have attended every one of the past six TICAD meetings. They have all been unique but something worth a special celebration happened in 2016, when TICAD took place on the African soil – in Nairobi – for the first time. Henceforth, the meeting will alternate between Japan and Africa every three years. The swaps are a symbol of the future we must build. That future spells out the fact that whatever geographical location we occupy in the world, our destiny is intricately tied. It is a paradigm shift that is much needed in the era of the SDGs.

Historians are likely to remember the launch of the SDGs as a turning point – the seminal moment in 2015 when shared prosperity became a fundamental way for organizing global development. Led by that spirit of the SDGs, we must invest our resources and energy in the realization that the traditional dichotomies of East and West, North and South, rich and poor, the bearers of knowledge and the receivers of it, must crumble. Through TICAD and other multilateral initiatives, we must continue to build an inclusive and sustainable development framework that leaves no one behind. That is the kind of framework that can advance Africa’s transformation while fostering prosperity across the world.

To get there, investments in human capital are fundamental. In the era of SDGs, anyone left behind in education and health anywhere in the world should be a concern for everyone else. First because these two issues are human rights issues, also because good health anywhere in the world provides global health security and good education builds global prosperity. Gains in women’s health, reductions in infant mortality or increased vaccinations are linked to stronger and more stable societies. Stable societies are engines for global growth – which brings us back to Africa development.

Much of Africa and some countries in Asia are some of the places where populations will continue to grow in the next few decades. In these areas, continued population growth can deliver a demographic dividend or a demographic disaster. That’s true across the portfolio of development, including global health.

Take HIV for instance, data has become clear that adolescent girls and young women are disproportionately affected by the virus. In sub-Saharan Africa, adolescent girls and young women (aged 15–24 years) accounted for one in five new HIV infections, despite being just 10% of the population. Urgent action to reduce HIV transmission in this population is vital to end the epidemic. If we stay the current course – with high infection rates and the current youth bulge in Africa – we will not end HIV by 2030. But if we invest vigorously and innovatively in responding to the challenges this group and other vulnerable populations face, we can end HIV as an epidemic for good. If we get it right, it can be a huge opportunity for the world to make a major step in ending the HIV epidemic. If we don’t, it will be a massive cost to all of us.

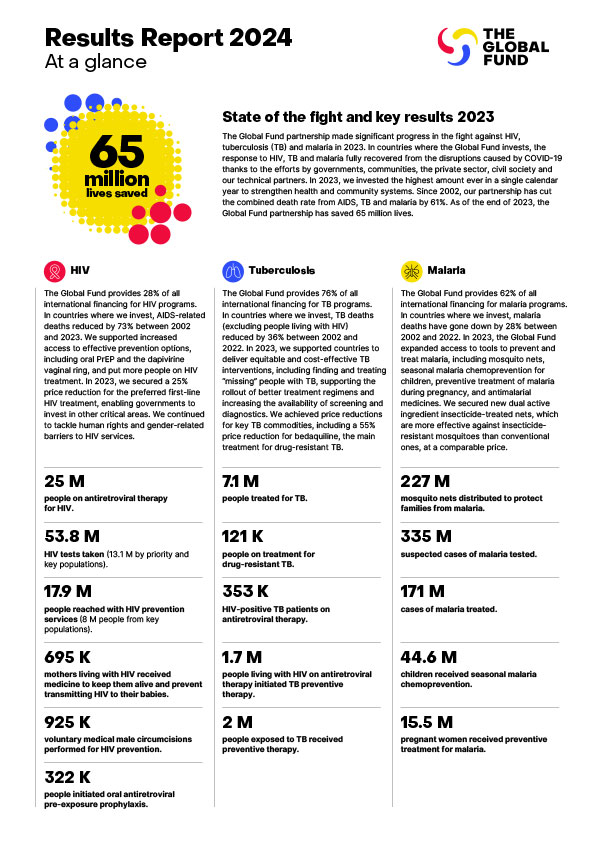

Both international and domestic investments in health are vital to ensuring that we do not lose the momentum we have built against HIV and other epidemics over the years. This year, the Global Fund seeks to raise at least US$14 billion to help save 16 million lives, cut the mortality rate from HIV, TB and malaria in half, and build stronger health systems by 2023. We are tremendously grateful to the people of Japan, who have already pledged toward this effort. Japan’s commitment of US$ 840 million will contribute to saving one million lives. We are also grateful to all other international donors who have committed towards this effort.

But to stay on track in the fight against HIV, TB and malaria and to build real sustainability that can end these epidemics, we must raise more domestic funds from countries that are more affected by these diseases. In the spirit of shared responsibility and global solidarity epitomized by TICAD, the international community must also continue the work they have been doing of investing in global health by supporting the Global Fund.

What goes for global health also goes for all other areas of development including ending environmental and security challenges. These two are the fundamental building blocks for securing and sustaining all the gains we make in global health and beyond. As African and Japanese leaders meet for TICAD, we must once again underscore the fact that leaving anyone anywhere in the world behind will have a huge cost for everyone globally. The leaders must emphasize that true commitment to multilateralism is the surest path to achieving shared prosperity. It is the way to give real meaning to the letter and the spirit of what it means to achieve sustainable development.

Dr. Donald Kaberuka is the Board Chair of The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria and the former President of the African Development Bank.

An abridged version of this piece appeared in The Mainichi, Japan.