Why the World Can’t Afford to Give HIV, TB and Malaria a Chance to Bounce Back

These three diseases kill half as many people now as they did 20 years ago. Those gains could be lost unless the world invests now.

A child born today in Japan can expect to live to more than 84 years of age. By contrast, a child born in Lesotho can expect to live to just 50 years – a gap of 34 years between the countries with the world’s longest and shortest life expectancies.

Much of this difference is due to the fact that infectious diseases like HIV, TB and malaria – largely contained in richer parts of the world – still kill millions in the poorest communities. Weak, overstretched health systems and a lack of access to the best medicines leave communities vulnerable to these and other diseases, which rob individuals of their lives, families of their livelihoods, and economies of productivity.

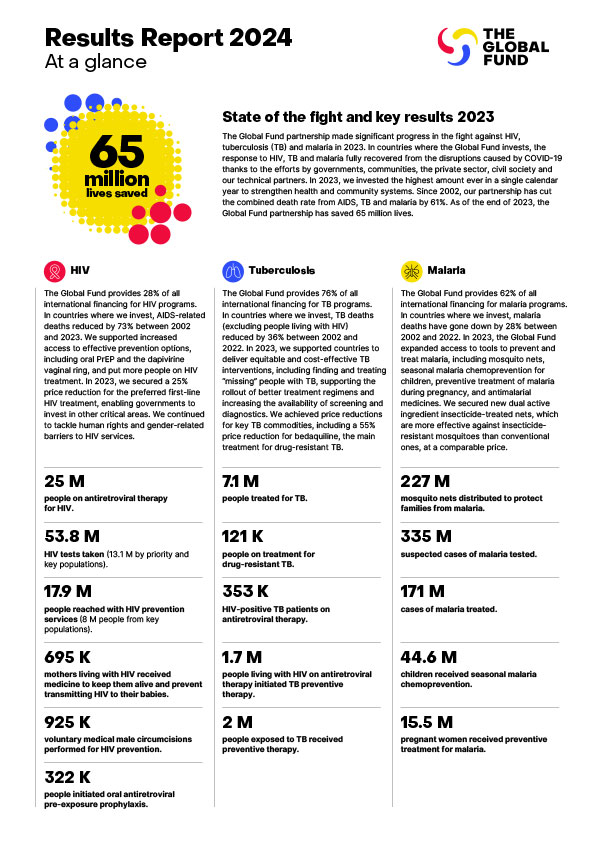

Since 2000, the world has made great progress against all three diseases. The combined number of people they kill each year has dropped by almost half – a decline of 70 per cent for HIV, 40 per cent for malaria and 30 per cent for tuberculosis.

One of the key reasons behind these gains is establishment in 2002 of the Global Fund. A partnership between governments, civil society, technical agencies and the private sector, the initiative mobilises funding for treatments, testing, bed nets and other preventive measures in the countries hit hardest hit by these diseases, most of which are low- and lower-middle income.

In the 20 years since its founding, the Global Fund has invested more than $55 billion (£48bn) in more than 100 countries, helping to save an estimated 50 million lives. For example, in Malawi, life expectancy has increased from 46 to 65 years in two decades. A significant element of that progress is from investments in HIV, TB and malaria.

A key part of the Global Fund’s success is its partnership with other health institutions, including the World Health Organization (WHO).

Our two organisations have a long and close relationship: initially, the WHO hosted the Global Fund at its Geneva headquarters, and has always had a seat on its board. For its strategies and funding allocations, the Global Fund relies heavily on the WHO’s technical expertise, data, leadership in setting norms and standards, and its relationship with Ministries of Health as the world’s leading technical agency for health.

This relationship was cemented further during the Covid-19 pandemic when the WHO, the Global Fund and other partners joined forces to create the Access to Covid-19 Tools Accelerator, to support equitable access to tests, treatments, vaccines and other supplies in low- and middle-income countries.

On the other hand, WHO has neither the resources nor the mandate to give countries the financial support they need to implement the policies, strategies and other technical advice it provides. That’s where the Global Fund comes in, bringing the financial muscle to support countries to implement the solutions that the WHO recommends.

A difficult fight ahead

Our partnership has been undeniably successful. However, even before Covid-19, progress against the three diseases was slowing, and the pandemic has now put the hard-won gains of two decades at serious risk.

A new report published last week shows that swift action is paying off. In 2021, once again, gains were once again made in the fight against HIV, TB and malaria and health systems are becoming more resilient.

But ending deaths from these three diseases will not be an easy fight. The situation is made worse by the global economic impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic and are now compounded by overlapping and intersecting crises, with war in Ukraine, soaring prices for food and energy in many countries, and the existential threat of climate change, evident in the twin disasters of drought and famine in Africa, and record floods in Pakistan.

With steep competition for limited resources, investments with the best returns must be prioritised. In the case of HIV, TB and malaria, it is hard to beat the high-impact and multidimensional returns from investing in health. A recent study shows that low-cost treatment for an adult with TB can lead to an additional 20 years of productive life. For the 1,300 children under the age of five who die every day from malaria, insecticide-treated netting costing as little as $2 can create a lifetime of opportunity.

That’s why the Global Fund’s triennial replenishment this next week must be seen beyond only the health benefits.

It is critical for mobilising the resources to protect the progress that has been made, and drive us towards the targets set in the Sustainable Development Goals to end the epidemics of HIV, TB and malaria by 2030. To help achieve those goals, The Global Fund is seeking $18bn for the period 2024 to 2026, which could help to save an estimated 20 million lives.

Covid-19 has shown that a health crisis is also an economic crisis. For the communities most affected by HIV, TB and malaria, this kind of disruption is entrenched and continuous. The benefits of addressing these diseases in terms of productivity, education and well-being are huge and immediate.

That means health is not a cost to be contained, but an investment to be nurtured – an investment in healthier and therefore more productive and resilient communities, societies and economies.

Ultimately, it’s not a question of whether the world can afford to invest in the Global Fund; it’s a question of whether it can afford not to.

Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus is director general of the World Health Organization

Peter Sands is executive director of the Global Fund to fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria

This op-ed was first published in The Telegraph