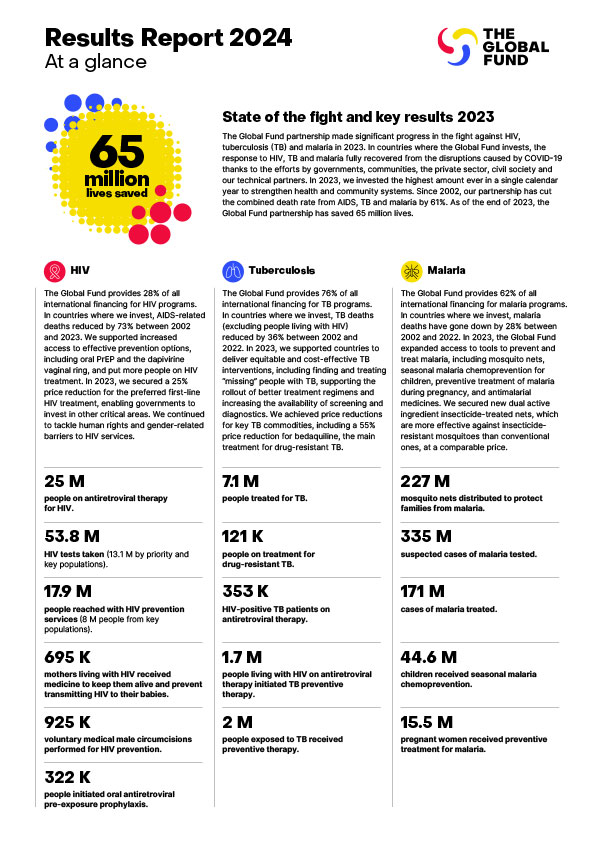

One Mozambican Woman’s Fight Against Malaria – “the Devil” That Took Her Husband’s Life

“Malaria is the devil that came to my house,” Celina Tembe says softly, her hand touching the head of her 3-year-old daughter, Manuela Manuel. In August last year, her 35-year-old husband, Manuel Maxaieie, came home late from work as a machine operator, tired and feverish. Celina said he should go to the clinic, but he insisted paracetamol would do, and the next morning he went back to work.

But at 3 p.m. the following day, his office called to say he was very sick and that they were sending him home. She took him straight to the clinic. They tested him for malaria and put him on treatment. But it was too late. That night, he died.

In those 36 hours, Celina lost her husband of 10 years, a man she describes as “strong, dark, full of energy.” Suddenly she was a widow, a single mother with three small kids, without an income.

Gone were their plans to open a small grocery store – half built behind where she sits. Instead, Celina put her energy into their small farm, growing cassava, corn, sweet potato and peanuts to feed her children and have something to sell. Gone were their plans to put glass in the windows of their small concrete house in quarteirão 22 community, Boane District, Maputo province.

Brushing away tears, Celina describes how she began to put her life together again, her energy focused on feeding her children.

But only six months after Maxaieie died, in February 2023, Cyclone Freddy struck. Her house was flooded, and the family had to seek refuge in an overcrowded school. After a week, they returned home to find everything covered in mud, their crops destroyed, and water everywhere.

With the water came the mosquitoes, and a week later Celina’s youngest child, Manuela, fell sick. Celina recognized the symptoms and rushed her to the clinic. Quickly diagnosed with malaria, she was treated and recovered in a week.

But then her oldest, Shalice Manuel, 9, got malaria too. She was much sicker and was in bed at the clinic and then at home for 15 days.

All this time, Celina struggled to provide food, making soup from the leaves of Tseké, a local plant.

Global Fund executive director Peter Sands talks with Celina Jorge Tembe and her children in Boane, Mozambique. Tembe lost her husband to malaria, and her children have also had the disease. Photo: The Global Fund/Tommy Trenchard/Rooftop

And Celina herself got malaria, needing the support of a cousin who lives nearby to look after her children while she lay ill.

Now, two months later, Celina is clearing the house and protecting the furniture, because today a team of women from the community will be spraying her house with insecticide. Indoor residual spraying is a method of controlling mosquitoes by spraying the interior walls with a mixture that leaves a fine coating of insecticide that is deadly to mosquitoes. Against the particular species most prevalent in Mozambique, it provides protection for about seven months.

This spraying program is funded through MOSASWA, a malaria elimination initiative jointly funded by the Global Fund, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and Goodbye Malaria.

Goodbye Malaria represents corporate philanthropy at its best. Nando’s, the international restaurant chain, sources chilis from Mozambique for its famous piri piri chicken. Through Goodbye Malaria, Nando’s provides not just funding, but also management expertise and leadership. Over the last eight years, MOSASWA partners have invested US$65 million in fighting malaria in this part of Mozambique, South Africa and Eswatini.

Mozambique has made dramatic progress since 2000 in protecting people from malaria, with deaths from the disease down by 67%. Yet the number of infections has stayed steady and is now on the rise. In 2021, this country of about 30 million people reported 10.3 million infections. However, in the part of Mozambique MOSASWA is active in, infections from the disease have been cut by a staggering 75% between 2018 and 2021 – averting over 300,000 infections.

Climate change is not the only factor threatening this progress. Mosquitoes’ increasing resistance to existing insecticides, and the malaria parasite’s increasing resistance to existing treatments are also having an impact. But the greater frequency of cyclones generated by the increasing warmth of the Indian Ocean is definitely driving surges in infections.

Members of a residual spraying team prepare to spray the home of Celina Jorge Tembe in Boane, Mozambique. The family has been heavily impacted by malaria. Photo: The Global Fund/Tommy Trenchard/Rooftop

Last week the Global Fund announced an extra US$1 million contribution from its Emergency Fund to MOSASWA to reinforce the response to Cyclone Freddy. This follows recent Emergency Fund contributions to fight malaria for Malawi, Pakistan and, in fact, Mozambique. When emergency contributions start becoming regular and frequent, it’s a sign that a different approach is needed.

After years of progress in the global fight against malaria, we risk going backward, putting more families like Celina’s at risk. It’s not that we don’t know how to fight this disease, nor that we lack the tools. Forty-two nations and territories have eliminated malaria entirely. The pipeline of new mosquito-control tools, medicines and diagnostics is stronger than it has ever been. The problem is money. The Global Fund represents 63% of all external funding for malaria, investing about US$1.4 billion per year. To put this in perspective, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles – by no means the largest hospital in the U.S. – has an annual budget of about US$5 billion.

Celina and her children have access to critical malaria-fighting tools – but this is not a given. In most parts of Africa, indoor residual spraying, which costs about US$18 per house, and lasts nine months, is considered too expensive. Elsewhere, we rely on insecticide-treated mosquito nets, which cost under US$3 and last at least two years. Yet we are struggling to fund the transition to the latest generation of mosquito nets, which combine two insecticides to combat resistance and are over 40% more effective in preventing infections. These new nets only cost about US$1 more than existing ones, but the Global Fund is buying over 150 million nets a year, so that’s a big difference.

Saying goodbye to Celina, it's hard to feel like we’re doing enough. We know how to protect her and her kids from this terrible disease. We know that climate change and resistance are going to increase the dangers. We could and should do more, and now.

This op-ed was first published in Forbes.