Taking a Smart Approach to Making Medicines in Africa Will Save Lives

COVID-19 shone a harsh light on global health inequities. Africa was last in the queue for all the lifesaving tools needed to defeat the new virus, including vaccines, tests, oxygen and personal protective equipment. Yet this is not a new phenomenon. It was several years after antiretroviral drugs (ARVs) for HIV became widely available in high-income countries that the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria and the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) were created to ensure broader access to these lifesaving medicines in Africa. Almost all the tests, medicines, vaccines and medical instruments used in Africa are manufactured elsewhere. This means that when there is a worldwide shortage or supply chains get disrupted, it is those in need in Africa who suffer the most. In a global health emergency, national priorities quickly surface, and those who can buy their way to the front of the queue do so.

African leaders have rightly concluded that ensuring better health security for their people means getting more of the medical tools they need manufactured on the continent. Through the Partnership for African Vaccine Manufacturing and arrangements with pharmaceutical companies, bilateral development partners, and multilateral agencies like Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance and the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness and Innovations (CEPI), there are now several vaccine manufacturing sites under construction in countries like Senegal and South Africa.

Although most of the current focus is on vaccines, there is also real progress on diagnostic tests and medicines. The Global Fund already buys antimalarials, insecticide treated nets for malaria and essential medicines from Africa-based manufacturers. In August 2023, the Global Fund, in collaboration with PEPFAR, Unitaid and the World Health Organization (WHO), issued a call for proposals for HIV rapid diagnostic tests manufactured in Africa. In October, the Global Fund, working with these same partners as well as UNAIDS, German Agency for International Cooperation (GIZ) and the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, hosted a public-private sector conference in Maputo, Mozambique, on HIV ARVs with a similar ambition.

As we progress with these projects, it is important to tackle the immediate obstacles while also thinking about longer-term sustainability, equitable access and universal health coverage.

One key factor is market demand. Demand for medical products can change dramatically as diseases evolve and competing alternatives emerge. Without some confidence about who will buy the product, and at what scale, private sector companies will not invest. Publicly funded manufacturing projects risk becoming redundant if their sponsors have been overly optimistic in forecasting demand.

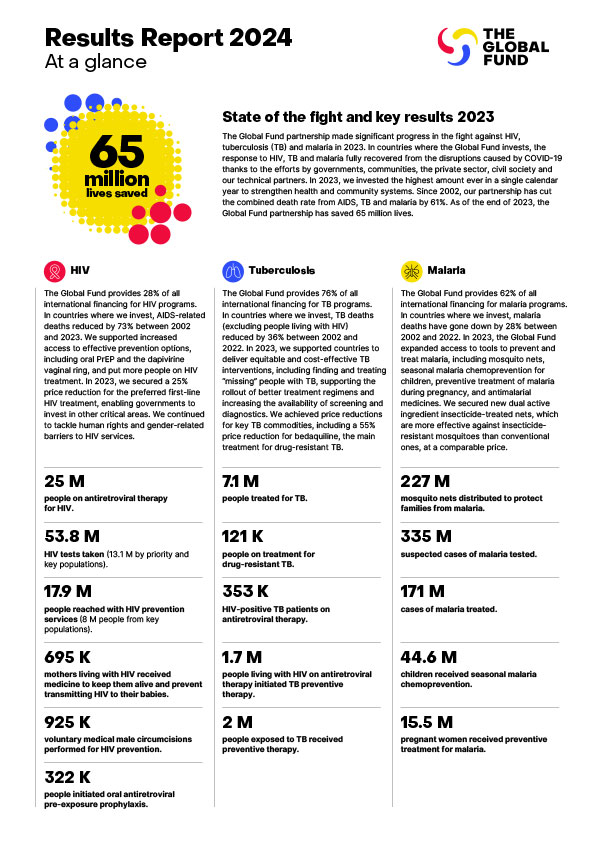

This is why the Global Fund has focused on high volume HIV and malaria products, such as HIV tests and ARVs, and insecticide-treated mosquito nets for malaria. In 2022, 51% of new HIV infections occurred in sub-Saharan Africa. In 2021, the WHO African Region was home to 95% of malaria cases and 96% of malaria deaths. PEPFAR and the Global Fund are the world’s biggest funders of HIV services and procurement. The Global Fund alone accounts for about half the worldwide market for insecticide-treated nets, and so can guarantee sustained demand for these products. In the longer-term, the success of African pharmaceutical manufacturing will depend on its ability to provide high quality products to a much broader range of purchasers across the region.

It is also critically important that African-manufactured products secure timely regulatory approvals so that multilateral agencies like the Global Fund can procure them. This is an immensely complex arena, since both products and manufacturing facilities need to be approved at a global level by WHO and at a national level by the national regulatory authorities. It is vital to ensure rigorous scrutiny of patient safety and product quality. Yet these approval processes can be extremely cumbersome and costly and it can take a couple of years or more to secure approval. No investment case can tolerate a factory not being able to sell the product for such a long time. So, for our call for proposals for HIV rapid diagnostic tests manufactured in Africa, the Global Fund is working with PEPFAR and Unitaid to pilot an accelerated process that builds on an assessment conducted by an Expert Review Panel convened by the WHO.

The creation of the African Medical Agency (AMA) could also make a huge difference. If products with AMA approval can be sold across the continent, that is much easier than securing 54 different national approvals. Yet the AMA is still at a relative early stage.

Sustainable development of regional manufacturing also requires investment in the broader ecosystem, including scientific and clinical research, regulatory capacities and equipment services. Above all, there is an acute need to invest in human capital, since scarcity of specialized skills is a huge constraint. Development partners have a critical role to play in this context.

Finally, there is the issue of competitive pricing. Efficient manufacturing of medical products requires significant scale, so African medicine manufacturers need to have access to regional markets, and for most product categories it will not be economically viable to have more than a few manufacturers serving the continent. The Global Fund takes a value-based approach for greater security of supply, and has adopted a total delivered cost model, taking account of logistics costs. But it will be important for African manufacturers to demonstrate cost competitiveness. While localized manufacturing is key to improving equitable access to medical products, so too are low prices. When millions of people in Africa are still denied access to lifesaving medicines because of affordability, it is hard to justify paying more than a very modest or transitionary premium for African-manufactured health products.

The story of local manufacturing of first-line tuberculosis (TB) treatments offers something of a cautionary tale. While there are very successful examples, in several countries local manufacturers used their political influence to secure national procurement deals at massive premiums to the global prices, while lapses in quality assurance contributed to the spread of drug-resistant TB. People with TB suffered as a result.

Such examples should not deter us from accelerating the development of African manufacturing of medical commodities. It simply means we should do this smartly, with an eye to the risks. At the Global Fund we are committed to catalyzing the rapid development of regional manufacturing, so the people of Africa can benefit from a better, more secure supply of high-quality, affordable tests, medicines and other medical tools. This is key to reducing global health inequities.

This op-ed was first published in Forbes.