Against A Foe As Formidable As HIV, Anything Less Than Victory Is Creating A Future Problem

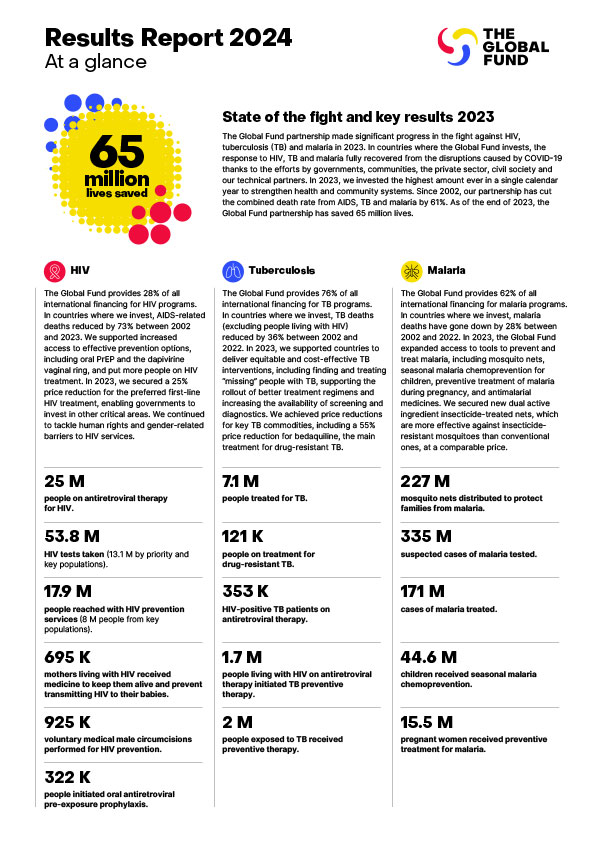

With another World AIDS Day behind us, we reflect on the nearly 40 million people who have lost their lives to this terrible disease. Yet we should also recognize the extraordinary progress we have made in combatting HIV and AIDS. Since 2002, in countries where the Global Fund invests, AIDS-related deaths are down by 72% and new HIV infections are down 61%.

By reducing the annual cost of HIV treatment from US$10,000 in 2002 to just under US$45 today, we’ve been able to massively expand HIV treatment, prevention and care. Now 24.5 million people are on HIV treatment in the countries in which the Global Fund invests, and we have reversed the course of the pandemic.

Yet the fight against HIV remains unfinished. In 2022, there were 630,000 deaths due to AIDS and 1.3 million new HIV infections. AIDS is still the biggest killer of women aged 18-45 in Africa. There are some 9 million people worldwide who are HIV-positive, but not on treatment. Without treatment, half of all children born with HIV will die by the age of 2.

To end a disease like HIV, we have to build more just and equal societies. Although we do not yet have a vaccine or cure for HIV, we have powerful tools to prevent infections and allow those living with the virus to have long, healthy and happy lives. Yet even the best biomedical tools are of limited value if the people who need them most cannot access them.

Key populations, such as gay men and other men who have sex with men, sex workers, trans and gender diverse people, people who inject drugs, people in prison, and their partners continue to be disproportionately affected by HIV. Their vulnerability is a direct consequence of stigma and discrimination, criminalization, and other laws and policies that undermine human rights.

The fact that in some parts of Africa adolescent girls and young women are several times more likely than boys and young men of the same age to be infected with HIV is not really a a biomedical issue. It’s a consequence of structural gender inequalities, including economic disempowerment, educational disadvantage and gender-based violence.

Diseases like HIV expose the ugly fault lines within our societies. Human rights barriers are the reason why — 35 years after the first World AIDS Day — we are still off track in ending HIV as a public health threat.

The Global Fund’s Strategy puts people and communities at the center of our work and commits us to do even more to tackle human rights-related barriers, gender inequality and health inequity.

In making this aspiration concrete, we are building on the success of “Breaking Down Barriers,” the pioneering initiative we launched in 2017 and through which we support 20 countries to develop and implement country-owned programs to address human rights-related barriers to health services.

By engaging health care providers, law makers and enforcers, judges, and parliamentarians, and by empowering communities, we have seen legal and policy changes and greater access to services. In these countries, investments in human rights programming have increased tenfold.

Over the entire Global Fund portfolio, our investments in such programs amount to over US$200 million. In the next grant cycle we expect to see that number increase and are adding four more countries to the Breaking Down Barriers initiative.

This year more than ever, World AIDS Day reminds us that the imperative to protect and promote human rights has never been more important. Across the world, in both rich and poor countries alike, we are seeing an alarming erosion of such rights. We are hearing the language of global solidarity and of our common humanity much less often. If we are to finish the job in defeating AIDS and deliver on the Sustainable Development Goal 3 (SDG3) objective of health and well-being for all, we must fight back.

In a world where it seems all too easy to dismiss the humanity of others, whether because of their gender or sexuality, their ethnicity, their religion, or because they’re a migrant or refugee, we must rediscover the spirit of global solidarity. The Global Fund partnership is proof that when the world comes together to make the impossible, possible, it can be done.

If the erosion of human rights is the biggest challenge we face in the fight against HIV, the second biggest might be complacency. With more countries achieving the UNAIDS 95-95-95 target (meaning 95% of HIV positive people know their status, 95% of those are on treatment, and 95% of those on treatment are virally suppressed), and fewer people in positions of power feeling personally at risk, it’s becoming more challenging to sustain the political will and mobilize resources to finish the fight. In a world where there are so many competing needs and crises, it is understandable that policymakers are tempted to switch focus and direct resources elsewhere. But slowing down now would be a huge mistake. In those countries where HIV and AIDS have been ignored or neglected, we have seen it resurge. Against a foe as formidable as HIV, anything less than victory is creating a future problem.

So, we must recommit to the SDG3 goal of ending HIV and AIDS as public health threats by 2030. We will not achieve this on the current trajectory. But we can achieve it, if we have the political will and muster the required resources. The global response to HIV and AIDS was a turning point in public health, an extraordinary expression of global solidarity that changed the way we think of people’s right to health. Now we must finish the task and achieve a world free of AIDS.

This op-ed was first published in Forbes.