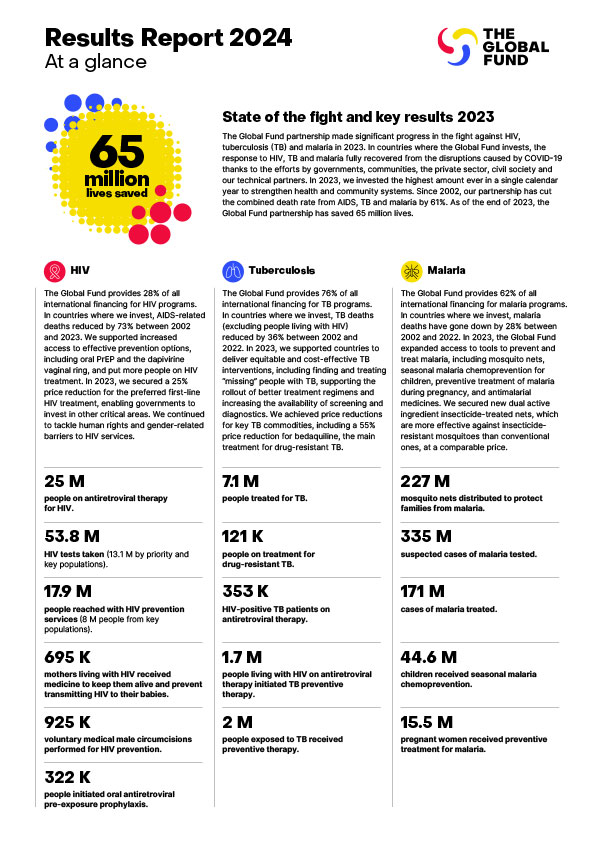

Despite being preventable and curable, tuberculosis (TB) continues to be the number one infectious disease killer. In 2023, an estimated 10.8 million people fell ill with TB worldwide and 1.25 million people died from the disease.

If the world seizes the opportunity of recent successes – renewed political commitment, strong results, and a combination of price reductions and new innovations – we can reinforce global health security and make a decisive shift toward ending this age-old disease. The Global Fund is the largest external source of financing for drug-resistant TB – an ever-growing global threat and a major cause of death from antimicrobial resistance worldwide – in low- and middle-income countries. Failing to invest to end TB means that the world will face an even more dire global health crisis. TB does not respect borders. The spread of TB anywhere poses huge risks for everyone, everywhere.

With a robust Eighth Replenishment, the Global Fund could reduce TB incidence and mortality rates by 32% and 60% respectively (between 2023 and 2029) in countries where the Global Fund invests.

TB has threatened humanity for too long. We must defeat this deadly disease together.

Long Seen as the “Pandemic of the Poor”, TB is a Threat to us All

Despite being preventable and curable, tuberculosis (TB) has regained its position as the number 1 infectious disease killer worldwide, causing 1.25 million deaths in 2023. As a respiratory infection prone to drug resistance, TB poses a looming threat to global health security.

Champa and Rekha: Fighting Tuberculosis Through Fear and Floods in Bangladesh

It started raining mid-morning – a light drizzle. Community health worker Champa Tidakar was prepared. She’d heard there would be a huge storm. Together with her husband, father-in-law, teenage son and young daughter, she gathered some non-perishable food. They built a barrier around their home and Champa moved a few precious items – including her stock of tuberculosis (TB) medicine – to a high shelf.

These Women Are Keeping Us All Safe From Infectious Disease

A health crisis anywhere is a threat to people everywhere. This is why investments fighting HIV, TB and malaria are so vital – not only to fight the world’s deadliest diseases, but also to ensure that health systems everywhere are equipped to detect and contain outbreaks before they spread. Women are most often the ones doing this vital work – keeping people everywhere safe from infectious disease. On International Women’s Day we celebrate these health heroes.

Equipped with Cutting-Edge Tools, Heroic Health Workers Lead the Charge Against TB in Iraq

For years, Dr. Bashar Hashim Abbas, manager of the National Tuberculosis Program in Mosul, Iraq, worked from unair-conditioned trailers, under bombardment and without adequate supplies and equipment to protect him from infection.

Chest Camps in Pakistan Bring TB Services to the People

On a cold winter day, Adnan Saeed and his brother Rizwan travel from their home to the nearby village of Chak 168 GB Sirāj, about an hour’s drive from Faisalabad, Pakistan. The temperature dips down toward 0 degrees Celsius; still, dozens of men, women and children gather around the tent, exchanging news and waiting to register for a tuberculosis (TB) screening and test.

Women at the Forefront: Providing Vital Care to Communities Caught in Crises

Natural disasters, extreme weather events, conflict and political instability can devastate local health systems, displace thousands of people and fuel the spread of disease. HIV, tuberculosis (TB) and malaria disproportionately impact people caught in crises – which is why more than one-third of Global Fund investments support communities and countries navigating complex environments and emergencies.