Pop-Up Booths to the Rescue in the Fight Against TB in Kenya

In August 2022 Josphat Muoki, a father of four from Nairobi, Kenya, discovered he had TB when he stopped at a pop-up screening station on a busy pedestrian bridge over Nairobi Central Railway Station. The bridge links the city and the industrial zone. Josphat works in procurement for an engineering company in the city, and often walks across this bridge to reach the companies providing spare parts.

On three occasions the community health workers manning the booth at the end of the bridge had tried to persuade him to go through the screening, but he had been too busy. But the fourth time he passed them, he was coughing, so he decided to do it.

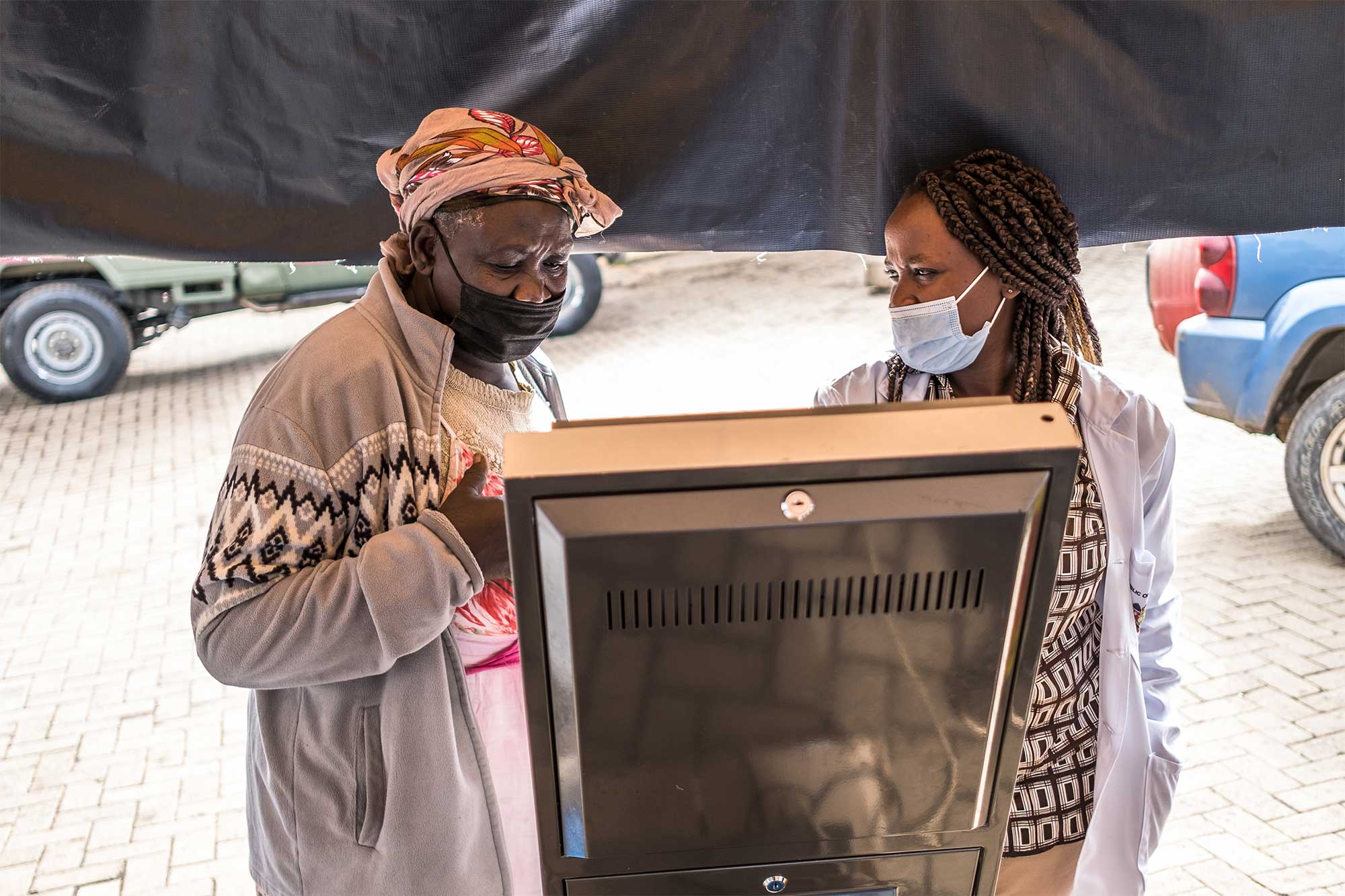

The screening took seconds. Josphat answered several questions on a touch-screen device that looked like a mini cash machine. Yes, he had a persistent cough. Yes, he was often hot and sweaty at night. The machine printed out what looked like a receipt telling him that he could well have TB and needed to be tested.

Given a mask, and accompanied by one of the community health workers, Josphat walked back across the bridge to get tested at the nearby laboratory. Within an hour he had his result. He had TB. That day he began treatment.

The six months of treatment were not easy. He stayed away from his family to avoid them getting infected. His wife and children were tested as part of the contact tracing program and were all negative. He kept working the whole time, wearing a mask, and keeping apart from his colleagues.

I met Josphat nine months after he discovered he had TB. He had finished his treatment in March, tested negative and was now restored to full health and back with his family. He was back at the screening booth to thank the community health workers and tell anyone passing why they should get screened.

Pop-up booths with “ATM” screening devices are just one example of the innovative approaches being used to find people with TB in countries like Kenya by partners such as SEMA Limited and Amref Health Africa. Since the disease disproportionately affects men of working age, sites with high foot traffic like the Nairobi railway bridge are perfect. Five booths such as this one, distributed across Nairobi, have already identified 721 people with TB and set them on the journey to treatment, therefore preventing more TB infections across the city.

Nikita Laureen, a community health volunteer, helps a patient to use a TB ATM at Kibera Health Centre in Kibera, Nairobi, Kenya. Photo: The Global Fund/Brian Otieno

Finding the people who have TB is still the biggest challenge in fighting this age-old disease, which still kills some 1.6 million people a year, making it rival COVID-19 as the deadliest infectious disease. In low- and middle-income countries, and among people of working age, TB is by far the biggest killer. The Global Fund, which provides 76% of external funding for TB programs, is constantly working with partners to pilot and scale up innovative approaches. In India, we have been using AI to identify hot spots. Through the Ending Workplace TB Partnership, we have engaged companies like Anglo American, Perenco or Kempinski Hotels to conduct workplace screening and diagnosis. This effort has covered 53 companies and more than 4 million employees to date. In countries like Timor-Leste or Tanzania, we take TB screening and diagnosis into remote villages using ultra-portable X-ray devices in four-wheel drive vehicles. In other countries, including Nigeria and the Philippines, we have combined testing for TB with testing for COVID-19.

The good thing about TB is that it is curable. The treatment takes several months and is more complicated and expensive if the person has a drug-resistant variant of the disease, but when the medicines are taken consistently, a person will become completely free of the disease. The bad thing is that untreated TB has a higher mortality rate than COVID-19 (much higher with drug-resistant TB), and it is highly likely that a person with untreated TB will infect someone else. One person with active, untreated TB can spread the disease to as many as 15 other people in a year.

Innovation to reach those most at risk is critical to winning the battle against TB. Josphat’s experience is a great example of how good execution of relatively straightforward and low-cost innovations can make a difference. Left untreated, Josphat’s health would have progressively deteriorated, and it was only a matter of time before he passed the infection to his family or a work colleague. Instead, he’s healthy, together with his wife and children, and back at work.

This op-ed was first published in Forbes.