Communities Affected by HIV Will Write the Last Chapter of the Disease

Dramatic changes have shaped the fight against HIV in the last 20 years. Highly effective antiretroviral therapy existed at the turn of the millennium – but only in rich countries. For people living in low- and middle-income countries – like my home country, South Africa – testing positive for HIV equaled a death sentence. I intimately know the desperation of those days: In 2001, I tested positive for HIV.

At that time, groups of mothers living with HIV would gather to write “memory books” – collections of stories that their children could hold onto after they were gone. These stories would profile family trees and capture the dying wishes of parents who sought to provide guidance for their children on how to navigate the future without them.

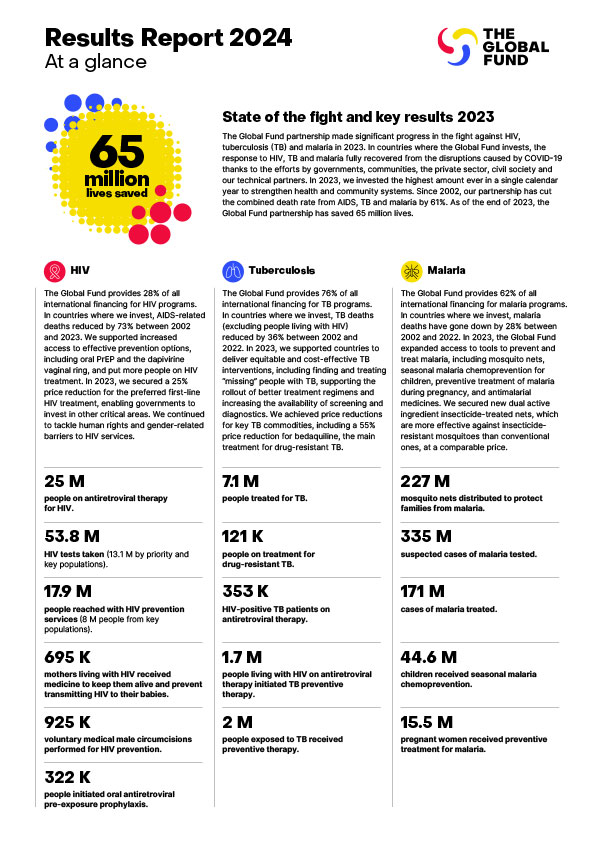

Of course, I refused to sit idle, waiting to die. Alongside communities of people living with HIV, I fought. Together, we poured into the streets, reciting our wishes. We called out governments for neglect and pharmaceutical companies for putting profits before people. We demanded equity and treatment for all. At the time, lifesaving antiretroviral therapy for one person cost nearly US$10,000 per year. Our fight led to the drastic reduction of the cost of antiretroviral drugs. Within no time, treatment ramped up. We moved from fewer than 50,000 people on HIV treatment in Africa at the time to more than 20 million today.

Despite all that progress, HIV remains a major public health threat. An erosion of human rights around the globe is making the disease more difficult to fight. More than 600,000 people still die of AIDS-related illnesses every year – all preventable deaths. Stark inequities, both within and between countries, fuel the virus, leaving key and vulnerable populations especially neglected in HIV responses. While there were 29.8 million people on lifesaving antiretroviral therapy globally in 2022, there are still close to 9.2 million people in the world who are living with HIV but who are not being treated.

And these challenges extend to other infectious diseases, too: While shorter and better-tolerated treatment regimens for TB now exist, we have much work to do to get those pills into the hands of people who need them most, often due to cost. Equitable access to TB diagnostics is also a challenge. While new, lifesaving vaccines to fight malaria are now available, they remain out of reach for many of the most in-need groups.

We need an enabling environment for everyone to have access to health services without any barriers. Our fight is far from finished.

To end HIV as a public health threat, we must borrow heavily from the lessons of the past. In those early days, it was easy to make rapid progress against the virus. Today, it is becoming harder to cover the last mile, to reach every person living with HIV who needs testing and treatment, because of the anti-gender rights and anti-human rights waves that are driving stigma and marginalization of people who live in vulnerable contexts. However, if we can learn from our beginnings and let communities be the indisputable leaders of the response, we can prevail.

We can end AIDS, but only if the communities affected by the virus are front and center of everything we do. That means investing in the tools they need to devise and deliver prevention and treatment programs for the communities most at risk. It means communities taking charge of designing, planning and implementing programs to fight the virus. These community-led responses and the necessary infrastructure to make the responses sustainable need funding and other support.

We must continue to invest in areas that create more and better opportunities for the most vulnerable, including young women and girls. We must ramp up support to communities in their efforts to fight restrictive policies and laws that criminalize key populations such as sex workers, men who have sex with men, trans and gender-diverse people and people who use drugs.

Above all, the whole global health community must rally behind that effort, by looking at every HIV program through the community lens and investing vigorously in that holistic approach, enabling communities to take the lead in all our HIV programming.

That community-centered approach can help to build a movement that will not only end AIDS, but will also make the world battle-ready for future pandemics. Many of the community members who sat to write their last words 20 years ago are the same ones who are going to hold the pen of the last chapters of HIV and other infectious diseases.

This op-ed was first published in Aftonbladet.