We Must Not Let Climate Change Derail The Fight Against Malaria

Photo: On 3 November 2022 in Jacobabad, Sindh province, Pakistan, Aneefa Bibi holds her 5-year-old daughter, Hood, who is experiencing fever and chest pains. These villages need the most attention after the recent floods as malaria, skin and other diseases are on the rise amongst the locals, especially children.

The world is at a defining moment in the fight against malaria. After years of rapid advances against the disease, progress stalled around 2015. Since then, the malaria community has faced a cascade of challenges, including drug and insecticide resistance, conflict, Covid-19 and climate change.

Thankfully, due to determined action by national malaria programs and their partners, we have been able to hold the line at a global level and ensure that the disease does not come roaring back.

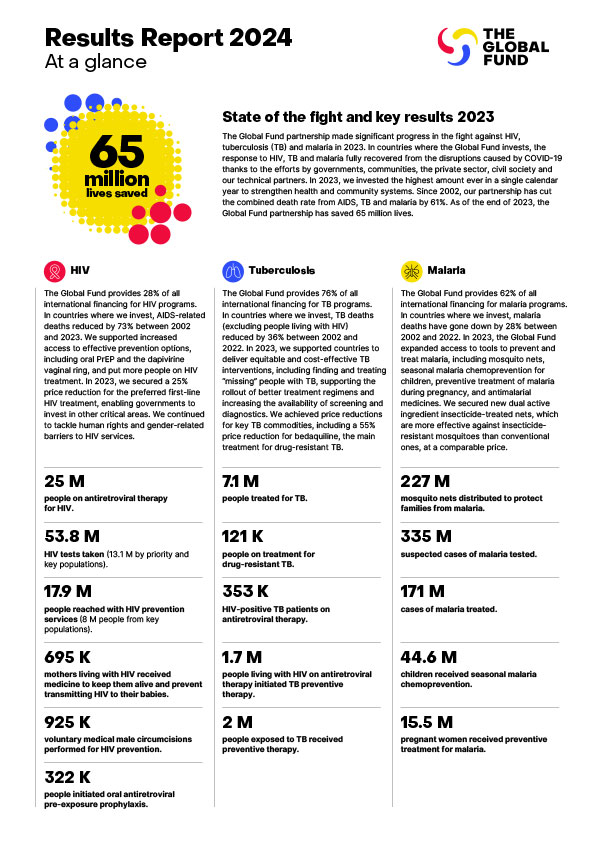

As the World Health Organization releases this year’s World Malaria Report, our confidence in that resilience is being tested. While the report shows that the world averted 2.1 billion malaria cases and 11.7 million deaths between 2000 and 2022, it also reveals that progress has ground to a halt, and in some places is reversing.

More than ever, we are at risk of losing our fight against this disease. There is no precise way to disentangle the impact of the different challenges confronting us as we battle malaria, since they interact and combine in multiple ways. But the impact of climate change is now increasingly alarming, with rising temperatures, more humidity, and more frequent and stronger extreme weather events expanding the range of malaria-bearing mosquitoes and leading to surges in the global number of infections. The communities most vulnerable to malaria are also the ones most vulnerable to climate change.

Africa, which bears 95% of the malaria burden, is also at the sharp end of climate change, despite contributing the least to it. Malaria is appearing in the highlands of countries like Ethiopia and Kenya, where previously it was too cold for mosquitoes. Floods and other extreme weather events are causing upsurges in infections, overwhelming health services and displacing communities in countries like Kenya and Somalia, which are currently experiencing El Niño rains, or Mozambique and Malawi, which were pummeled by Cyclone Freddy earlier in the year. Such extreme weather events also destroy the farms of the rural poor, increasing child malnutrition, which in turn exacerbates the impact of malaria. Malnourished children are much more likely to die from this disease.

The increasing frequency of extreme weather events is causing havoc on the fight against malaria in many other low- and middle-income countries beyond Africa. Take Pakistan, which experienced calamitous floods in 2022 that led to a massive surge in malaria cases. According to the World Malaria Report, of the 5 million additional cases observed between 2021 and 2022 worldwide, 2.1 million occurred in Pakistan. Incremental deaths from malaria in Pakistan far exceeded direct deaths from the floods.

The indirect effects of climate change are also having a powerful impact on the dynamics of the disease. Increasing competition for resources like water and land fuels conflict, which in turn disrupts programs to control mosquitos and treat those infected. Since prompt diagnosis and treatment is the key to avoiding severe disease and death, reduced access to health services has an immediate impact. The alarming spread of Anopheles stephensi, a malaria-carrying mosquito that thrives in urban areas and is highly resistant to most insecticides, may also be linked to climate change.

We must urgently respond to these early indicators of climate change’s impact on malaria, and on global health more generally. Unless we take action now, malaria could resurge dramatically, wiping out the hard-won gains of the last two decades. As the world gathers in Dubai for COP28 this week, we must seize the opportunity of the climate conference's first Health Day to intensify the focus on health as a critical component of the global response to climate change. An equitable response to climate change must include urgent action on global health, and on malaria specifically. Few have contributed less to carbon emissions than a small child in rural Africa. Yet few are more exposed to the life-threatening impact of climate change than children.

Implementing a comprehensive response to the impact of climate change on health will require urgent action on multiple fronts, including pre-emptive intervention to reduce the threat of the most climate-sensitive diseases, such as malaria; improving the resilience of health systems to climate change; and reducing the carbon emissions from health facilities and supply chains. We need further research to resolve the many unanswered questions about exactly where and how climate change will affect human health, but cannot wait until we have all the answers. We must act and improve our understanding in parallel.

We must also forge new partnerships that blur the distinctions between human health, climate, animal health and food security. A “one health” approach that recognizes these interdependencies is critical. Additionally, we must ensure that our interventions reinforce not just formal health systems, but also the community systems that play such a crucial frontline role in serving the poorest and most marginalized.

Over the last two decades we have made huge progress in the fight against malaria. But now we are at a crunch point. We have powerful tools—including innovations like dual active ingredient bed nets, seasonal malaria chemoprevention and vaccines—but need greater political will and more money to deploy them rapidly and at scale. Climate change and increasing resistance to insecticides and malaria treatments will make the task immeasurably more difficult. Delay will cost lives and money. Already, more than 11,000 people die from malaria each week, mainly pregnant women and young children from the very poorest communities in the world. To fail to act, and watch this number increase, would be more than a tragedy. Malaria is a preventable, curable disease we know we can beat, because many countries have already done so. We should use the threat of climate change as the spur to redouble our efforts to rid the world of this terrible disease, one of humanity’s oldest enemies.

This op-ed was first published in Forbes.