TB: No Longer the Forgotten Pandemic?

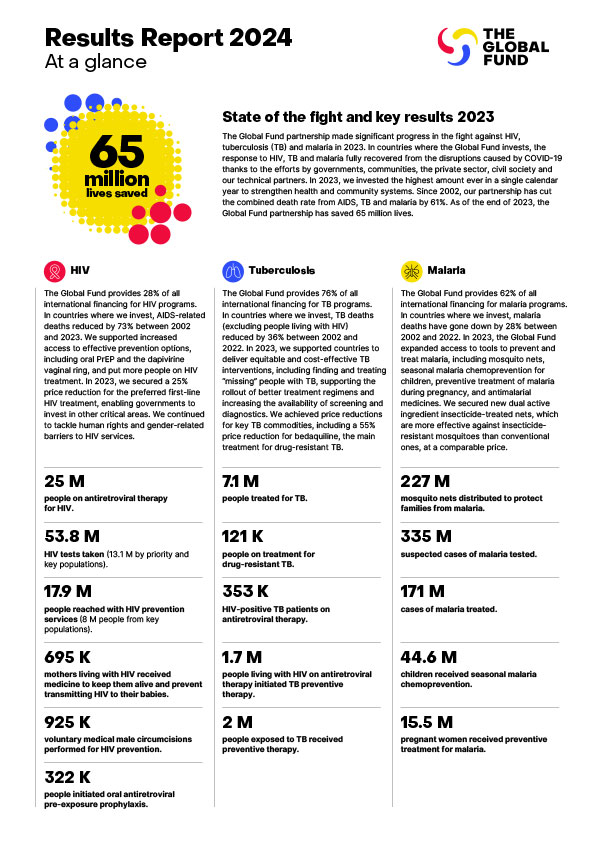

For far too long, TB has been “the forgotten pandemic”: killing millions, but attracting a tiny fraction of the attention and resources that have been devoted to COVID-19 or even HIV. Yet now the fight against TB has remarkable momentum. In many countries, the setbacks from COVID-19 have already been more than reversed. With advancements in TB prevention, diagnosis and treatment tools, with significant reductions in the prices of some key interventions, and with the confidence brought on by strong results, comes real hope of possibility and progress.

Across many of the countries most affected by TB, we are seeing unprecedented determination to beat this terrible disease. In countries across the globe, heads of state and government are displaying extraordinary political leadership and commitment to end TB for good.

Never before have so many people with TB been diagnosed and put on lifesaving treatment. In 2022, 7.5 million people were newly diagnosed with TB (and the preliminary results for 2023 are even more promising). This is the highest number since WHO began global TB monitoring in 1995. And yet, some 2.5 million people get TB every year and are not diagnosed. Not only do they suffer – and 1.3 million people died of TB in 2022 – but they also risk infecting others. Expanding diagnosis and treatment is key to cutting the death toll and the number of new infections.

In 2023, the Global Fund secured a 20% reduction in the price of the most commonly used molecular diagnostic test and a 55% reduction in the price of a key treatment for multidrug-resistant TB. Given the immense gaps in funding for TB – and the Global Fund represents over 75% of all external funding for TB – such cost reductions are crucial to enabling countries to continue to scale up testing and treatment. So too are the rollout of alternative diagnostic approaches, such as digital X-rays, and the deployment of a broader range of treatment and prevention options. Looking ahead, there are encouraging signs that – over 100 years after the development of the BCG vaccine, which now provides very limited protection – we may at last have more effective vaccines in sight.

But while progress against TB takes medical innovation and financial resources, these alone are not enough. The reason TB has been too often forgotten is that it is the pandemic of the poor and marginalized. Fighting TB entails tackling deep social inequities that make people more vulnerable to the disease and less able to access care. People living in crowded conditions, including those in informal settlements or in refugee camps, are more likely to get the disease. People who are undernourished, or who live in areas of high pollution, are less likely to survive it.

Successful TB strategies put the people and communities most affected by TB at the center of the response and display a willingness to confront the inequities that drive the disease.

Across the countries most affected by TB we are seeing unprecedented commitment to deliver against ambitious targets to end TB. For example, India, which has the world’s largest TB burden, with some 27% of worldwide cases, is targeting TB elimination by 2025. In 2022 India treated 2.3 million people for TB, up from 1.7 million just 5 years before. And in Indonesia, the country has stepped up domestic resource commitments to their TB program in recent years. As a result, Indonesia has been able to increase the number of people treated for TB from 339,000 in 2021 to 709,000 in 2022.

TB outreach workers form the backbone of Nigeria’s fight against tuberculosis. Photo: The Global Fund/Andrew Esiebo/Panos

Nigeria is another example of where political leadership and a robust and comprehensive plan are delivering results. The number of people treated for TB in Nigeria has nearly tripled over the last five years, from 105,000 in 2017 to 286,000 in 2022. The country is developing a strategic approach to ensuring equity and combating TB-related stigma and discrimination (about 25% of TB patients have reported being stigmatized in health facilities and 50% have reported stigma in the community). Through positive messaging, and the engagement of community leaders, educators and religious leaders, the government, together with community-based actors and private sector providers, is seeking to create a more supportive and informed environment, making it easier for those most at risk to access the health services they need.

Given acute fiscal constraints, and a multitude of competing health priorities, the level of political commitment to end TB now being demonstrated – in some of the most affected countries leading from the front – is all the more admirable. Yet the overall fight against TB still depends heavily on the support of global partnerships like the Global Fund, the Stop TB Partnership and WHO, as well as on bilateral partners like USAID.

Now is the time to step up, build on current momentum and accelerate progress. For far too long, TB has been “the forgotten pandemic,” or the “pandemic of the poor.” Now we can make it “the pandemic of the past.”