Empower African Youth So They Can Put an End to AIDS

When AIDS swept across Africa at the end of the last century, many of our governments were denying or downplaying the problem and it was the young people who mobilized. Large numbers of them were affected so they gave their energy, and even their lives, to fight a scourge which offered little hope of survival before antiretroviral drugs became widely available. They organized into associations and demanded that the world grant them the right to drugsand health care. Their fight was a resounding success.

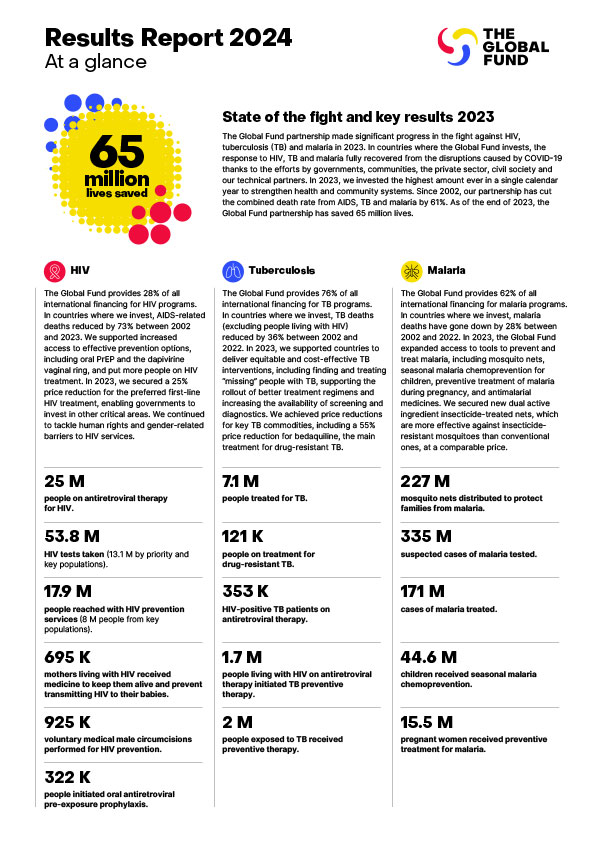

Today, with the support of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria and other partners, most African countries are running major programs to combat the disease. The programs include health care, the distribution of antiretrovirals and preventive products, and responding to the stigmatization of and discrimination against HIV-positive people. The results are encouraging. Since 2010, West and Central Africa has managed to reduce by 50 percent the number of new HIV infections and AIDS-related deaths.

This generally positive picture does, however, have a darker flip side: in Africa, young people aged 15 to 24 are still the most HIV-vulnerable group. Young women face harmful gender norms that reduce their ability to protect themselves against HIV and AIDS. Such norms also put them at risk of transmitting the virus to their children through lack of access to prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) treatment. Young people under the age of 25 may face laws, customs and social structures that exclude them from effective HIV prevention education. Every week, over 300 teenagers in West and Central Africa become HIV-positive, and many are unaware of it. For example, in my country of Cameroon, only 4 out of 10 teenagers know their HIV status. Yet knowing one’s serostatus is an essential step in benefiting from antiretroviral treatment and other health care services. As for children under the age of 14, the situation is of even greater concern. In West and Central Africa, two thirds of HIV-positive children do not receive any paediatric antiretroviral medication at all. In addition, almost half of HIV-positive pregnant women do not have access to PMTCT, which explains why one quarter of the world’s HIV-positive children live in West and Central Africa.

And yet, while HIV continues to wreak havoc among the under-25 age group, young people are, paradoxically, the population that is the least frequently consulted or listened to at the national and regional levels regarding matters related to sexual health and HIV. Yesterday’s young people, those who were at the helm of the first response to HIV/AIDS, are now parents, elders and leaders who manage HIV/AIDS programs and are barely receptive to this major, current, and timeless issue in the response to HIV and AIDS. The participation of the most affected communities at all levels of the HIV response that our elders built by winning hard-won battles, is still the most important but least acted upon principle in the fight against AIDS, as far as young people are concerned. We will only succeed in eliminating the disease if the leadership is passed on from one generation to the next and by training and empowering young people so that they can become fully involved in the response. This is essential for two reasons: This is necessary for two reasons: Firstly, without the input of young people, national programs and development partners struggle to identify HIV and AIDS needs because HIV-positive or at-risk young people are not a homogeneous population. Rather, they are interconnected groups with different needs: young girls, urban youth, adolescents from remote areas, teenagers who have dropped out of school, young migrants or refugees, or young populations made vulnerable by stigma and discrimination. Secondly, if we fail to identify the needs, programs will be unable to address all adolescents and young people using approaches that suit each of the different groups. For example, some young people are afraid to go to their local health center for HIV screening because they fear being recognized or stigmatized. Whereas they would turn to more informal structures, such as youth associations, to obtain self-tests to use at home.

Without the essential contribution of young people, we risk sacrificing our common dream of putting an end to AIDS. Indeed, the more a country, a culture or a program excludes HIV-affected communities from decision-making on sexual health and HIV, the more frequently the disease is transmitted and is therefore able to persist. In Africa, those communities are predominantly young people.

The situation requires more targeted investments in PMTCT, paediatric antiretrovirals, youth education on gender and HIV prevention, anti-stigma and anti-discrimination programs, and strengthening the leadership and institutional capacity of youth-led organizations. All the above are essential if we are to maintain the gains of the past and secure our future. And they must be built, implemented and evaluated with, by, and for young people.

We are the future of Africa. If nothing is done, many of us will continue to die due to lack of appropriate health care, medication and prevention. Unless urgent, concerted action is taken with us, for us and by us, many of us will be condemned to a lifetime of living with a now-preventable virus. The road to eliminating HIV and AIDS began with yesterday’s young people. And it will end with today’s young people. They will put an end to the epidemic and enable the emergence of the first AIDS-free generation in Africa in half a century, if their voices are heard and if they participate fully in the response.

This op-ed was originally published on Jeune Afrique.