Why Health Should Be at the Heart of the Climate Agenda at COP29

When I visited Dhaka in July this year, the city was wrapped in the thick humidity and heat of the monsoon season. The air felt heavy and warm as I walked with a community health worker through the winding, makeshift neighborhoods of one of the huge informal settlements that ring Bangladesh’s capital.

I arrived at the settlement well aware of the social, economic and health-related risk factors that have fueled the spread of tuberculosis (TB) for centuries. But when every single TB patient I spoke with shared that they had been driven to Dhaka by the consequences of extreme weather or failing farmlands, the urgent need to place health as a central focus in climate policy was made starkly clear. Health must be considered integral to climate adaptation and resilience-building efforts if we are to address the compounded threats of climate change and disease.

Bangladesh is one of the most climate-vulnerable countries in the world. Much of the country lies on a vast river delta, making it prone to flooding and rising sea levels. Increasingly powerful cyclones are destroying homes and crippling essential health infrastructure. Saline intrusion from seawater is rendering coastal farmland barren, contaminating vital sources of fresh water and – along with droughts and shifting rainfall patterns – degrading agricultural productivity.

The International Organization for Migration estimates that 70% of people living in Dhaka’s informal settlements moved there to flee some sort of environmental shock. With limited job opportunities and low-paying work, climate migrants often don’t have enough to eat and live in incredibly confined and crowded conditions. TB thrives among vulnerable, undernourished people packed tightly together. Recognizing and prioritizing public health challenges such as this within climate action plans – especially at global summits like COP29, which is taking place now in Baku, Azerbaijan – can equip health systems to better mitigate the risk of disease outbreaks in vulnerable communities impacted by climate change.

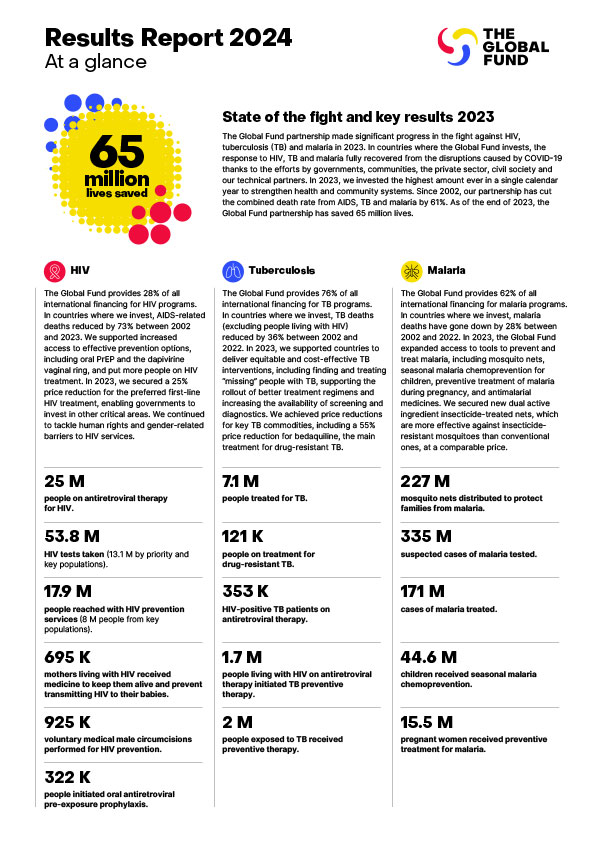

The impact of climate change on vector-borne diseases like malaria and cholera is already evident. Yet it also has a less directly visible knock-on effect on diseases like TB. In climate-vulnerable countries around the world, mass displacement from extreme weather is leading to overcrowding and poor living conditions that raise the risk of TB transmission.

Displacement can also cause people to interrupt their TB treatment, leaving them infectious for longer and at risk of developing drug-resistant TB, which is much more difficult and costly to treat. Food insecurity and poverty caused by climate change can worsen the health outcomes of vulnerable populations affected by the disease, as undernourished people are much more susceptible to TB. In 2023, undernourishment was the leading risk factor for TB infection in many of the 30 countries with the world’s highest TB burdens.

Climate change also undermines the capacity of health systems to support and protect people, which, in turn, hinders countries’ efforts to fight TB, HIV and malaria – three of the world’s deadliest infectious diseases. In places like Dhaka, an influx of climate migrants is straining already stretched health systems. This is not unique – health systems in many climate-vulnerable countries are being put under stress. In Malawi, torrential rains from Cyclone Freddy in 2023 swept away essential health data, medical supplies and infrastructure – leaving many people exposed to public health risks and disease. Only by embedding health considerations in climate responses can we support communities struggling with the dual burden of climate and health crises, prevent disease outbreaks and climate-proof health systems.

COP29 is an unmissable opportunity to intensify efforts and resources to confront the health impacts of climate change. Currently, less than 1% of multilateral climate funding goes to health – a startling disparity that risks undermining efforts to combat diseases exacerbated by climate change. By bridging this chasm, we can support countries to defend their communities from climate-driven health threats, particularly diseases like HIV, TB and malaria.

Health must be placed at the heart of climate discussions, metrics, and Nationally Determined Contributions (national plans and commitments made by countries under the Paris Agreement, a legally binding international treaty on climate change). Prioritizing and increasing investment in climate-health initiatives will protect the world’s most vulnerable populations, ensure that health systems can withstand climate shocks, and unlock benefits for global security and economic stability.

Leaving Dhaka, I watched Bangladesh from the air – a breathtaking patchwork of rivers, fields and densely packed urban areas, surrounded by the waters that both sustain and threaten it. Low- and middle-income countries like Bangladesh are suffering the brunt of a crisis they did little to cause, bearing the weight of climate change’s harshest impacts as it adds new challenges to their HIV, TB and malaria responses.

We must act decisively to address this injustice. By mobilizing more financing for climate-resilient health systems and enshrining health as a central pillar of the climate response, the world can support vulnerable communities on the front line of climate change, fuel the fight against the deadliest infectious diseases and build a healthier, more secure future for all.

This op-ed was originally published on Forbes.