In Rural India, High-tech Vans Find "Missing" TB Patients

Every year, approximately 10 million people fall ill with tuberculosis, but only 6 million are identified. The rest are “missing”– undiagnosed, untreated or unreported to the health systems. Missing TB cases and drug-resistant TB are challenges in fighting the disease, and pose a threat to global health security.

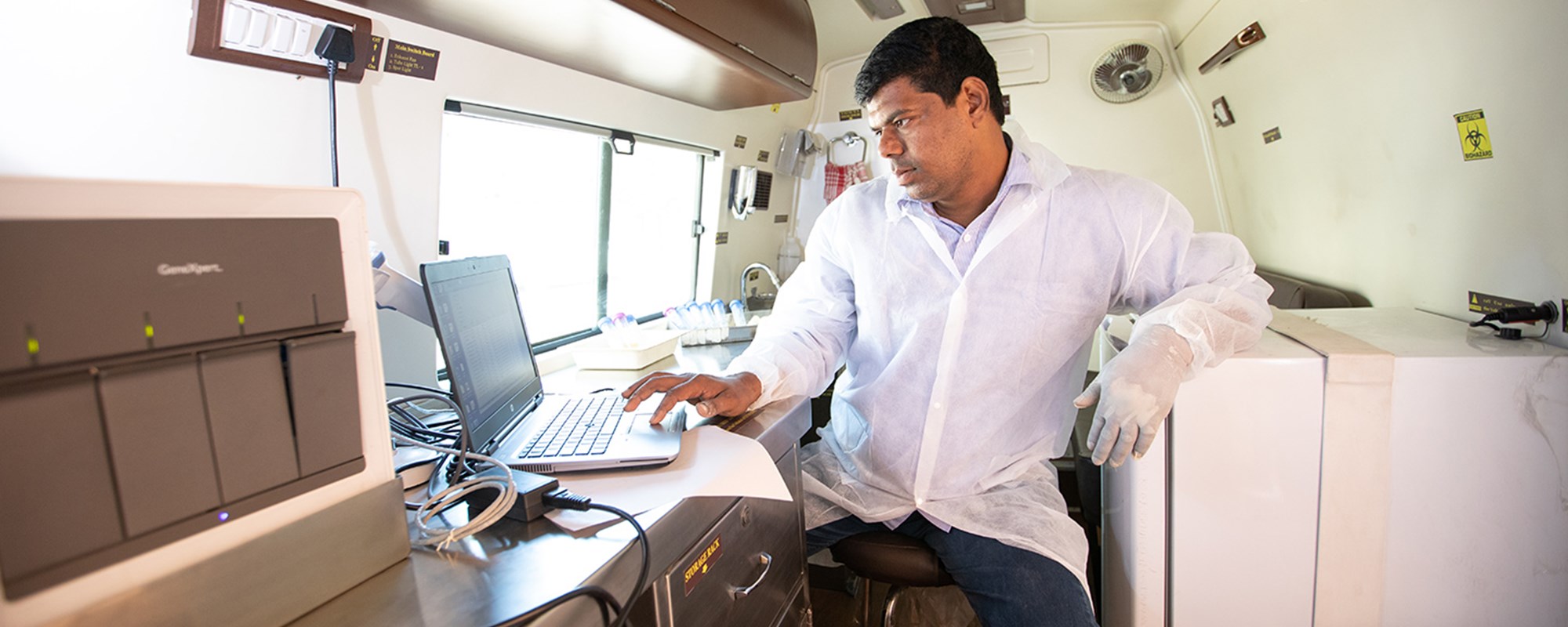

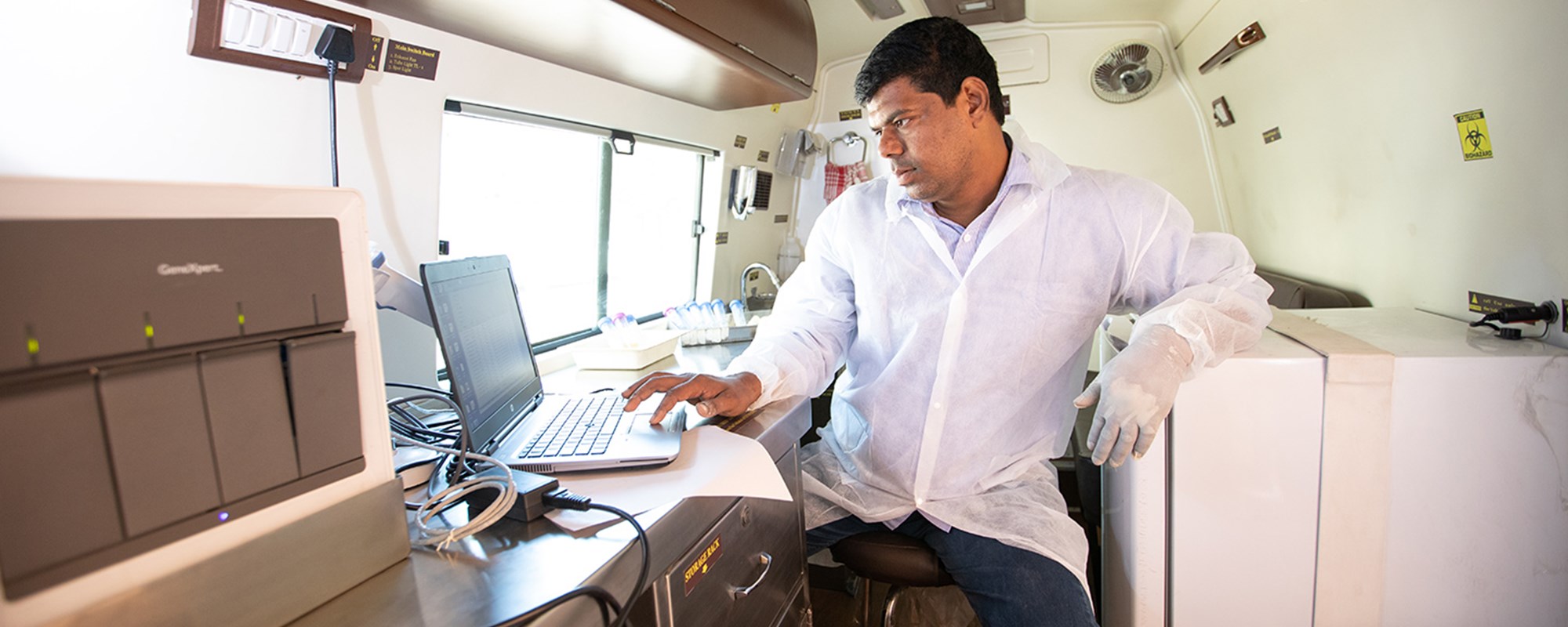

The Global Fund partnership is deploying cutting-edge technology to find missing TB patients. In India, home to the largest TB epidemic in the world, a fleet of specially equipped vans is bringing molecular-based diagnostic tools to rural areas and hard-to-reach communities to improve case-finding and access to health services. And the initiative is paying off.

On a recent morning, a van arrived in a farming community 100 kilometers east of Mumbai with eye-catching messages on its sides: “TB Test on Wheels!!! Taking TB Diagnostics Closer to the Public!!!”

It pulled into the parking lot of the local hospital, and technicians got to work – identifying TB patients so they can be put on treatment. With its temperature-controlled interior and high-tech equipment, the van stood in contrast to the outdated hospital in Rajgurunagar.

Inside the vehicle sat a GeneXpert machine, a sophisticated molecular technology that is more accurate and yields much faster results than traditional TB diagnosis methods, like smear microscopy. Using sputum samples, the machine can detect the DNA of tuberculosis bacteria, which allows patients to be put on treatment earlier and reduces the risk of transmission. In Rajgurunagar, it used to take eight days before the patient would get the results, but the van has cut the waiting period to a matter of hours.

“Technology is very important to fight TB,” said Doctor Geeta Kulkarni, medical superintendent at the Rajgurunagar hospital. She said TB case notification in her district has increased by 30 percent in the last year thanks to the use of GeneXpert machines and other tools to improve searching for, diagnosing and treating all forms of TB.

“Drug-resistant TB is a big problem in India, so to tackle the disease we need to find patients as early as possible. This is where the van comes in,” Kulkarni said, adding that of 40 diagnosed cases of TB in the area every month, two to three were multidrug-resistant cases.

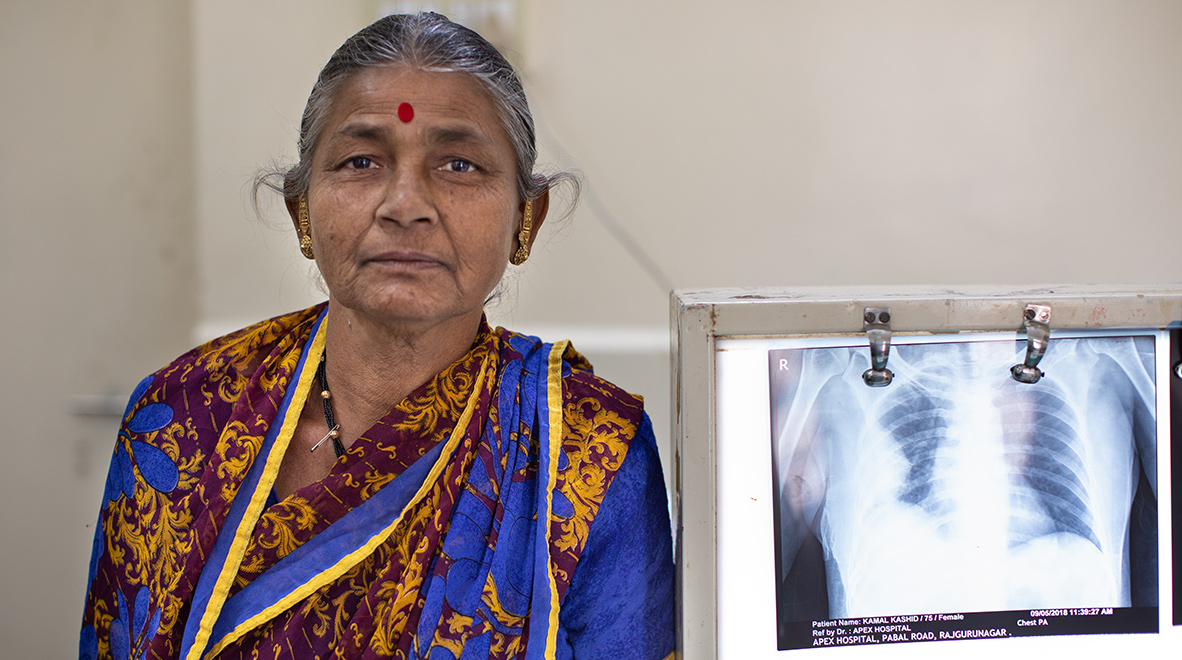

Kamal Kashid, 75, had been suffering from a cough for as long as she could remember, but did not know what was causing it. After she got too weak to work in her village’s fields of onions and grains, she was admitted to hospital. Kashid, who cannot read nor write, was diagnosed with TB by the van’s GeneXpert machine and was immediately put on treatment.

“I am so happy to be cured, and that there is a public system where we can go and be taken care of, free of cost,” said Kashid, who completed her TB treatment in October. “I have two daughters and they are both teachers,” she added proudly.

Tuberculosis, which affects mostly the poor and malnourished, and people with weakened immune systems, is a major health challenge in India. Every year, around a million people with TB in India are missing. The Global Fund is supporting India’s goal to end TB by 2025.

Deploying technology is at the center of a global initiative to find and treat an additional 1.5 million missing patients by the end of 2019. The work, which is being implemented in 13 countries, is supported by the Global Fund, WHO and the STOP TB Partnership. All these countries are using innovative case finding approaches, including more sensitive diagnostic tests and engaging the private sector and community-based groups.

The Global Fund has financed the purchase of 1,173 GeneXpert machines in India, which are being used in vans and health facilities. The vans are ideal for reaching vulnerable populations, including tribal communities that lack modern equipment or have no public health centers at all.

Each van travels with a lab technician, and is equipped with a cooler and a generator. Gopinath Danane, the driver of the van visiting the hospital in Rajgurunagar, said he sometimes spends up to five hours to reach remote communities.

Bringing diagnostics and treatment closer can make a huge difference for tuberculosis patients. Unable to make long, harsh journeys to clinics, many patients skip treatment, start taking medication too late or consult a local doctor who may not be qualified to diagnose or treat TB – particularly a drug-resistant strain. When patients don’t complete their treatments, they stay sick, spread disease and give drug-resistant strains of TB the chance to develop.

Kavita Shagul, 24, was diagnosed a year ago with TB, which also struck members of her family. “I had to quit my job working at a motorcycle parts store,” she said. “Now I am healthy and will look for a job again.”

Dr. N. D. Deshmukh, a senior public health official in Pune district, said science was essential to ending TB, but that technology alone will not do it. Also necessary is nutritional support and old-fashioned care. Patients need counselling, motivation, and sometimes a good listener.

“TB patients and their families need human support,” he said.